Mrs. Donoghue’s Journey

The Scottish Council of Law Reporting is delighted to be able to reproduce in amended form “Mrs. Donoghue’s Journey” — a fascinating paper originally prepared and presented by Mr Martin R. Taylor QC.

Mr Taylor is a distinguished lawyer — a retired Canadian judge, now in practice as an arbitrator in Vancouver, and a member of the Court of Appeal for the Cayman Islands. His enthusiasm for the famous Scottish case of Donoghue v Stevenson 1932 S.C. (H.L.) 31 is such that he organised, along with others, a “Pilgrimage to Paisley” in 1990 to celebrate its role in the development of the law of negligence.

The 1990 pilgrimage was sponsored by the Canadian Bar Association, the Faculty of Advocates and the Law Society of Scotland. The Conference was organised in Canada by a committee of alumni of the University of British Columbia Faculty of Law and in Scotland by a committee of the Old Paisley Society. The culmination was the Paisley Conference in September 1990 held in Paisley Town Hall and attended by over two hundred judges, lawyers and academics. The event was a huge success and it left a lasting legacy in the form of “The Paisley Papers”.

Mr Taylor’s original article forms the keynote piece in Donoghue v Stevenson and the Modern Law of Negligence which contains The Paisley Papers — The Proceedings of the Paisley Conference on the Law of Negligence. The Papers were presented by a number of leading commentators and were edited by Dean Peter T. Burns QC. They were published in 1991 by the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia under the supervision of Susan J Lyons the associate editor.

The Scottish Council of Law Reporting is most grateful to Mr Taylor and to the publishers for allowing it to reproduce these materials as a companion resource to Donoghue v Stevenson. The full report of the case is available on this SCLR website, as are digital images of the original court documents.

Sandy Wylie QC, 2004

MRS. DONOGHUE’s JOURNEY1

Martin R. Taylor QC

Originally subtitled “An Orientation as to Time and Place with Words, Music, Pictures, and Artefacts.”

It was sixty-two years ago — on Sunday evening, August 26, 1928 — that Mrs. May Donoghue of Glasgow, a person of modest means but much determination, passed by Paisley Town Hall on her way to the centre stage of legal history.

Her immediate destination was the Wellmeadow Café, a teashop at 1 Wellmeadow Street, operated by Mr. Francis Minchella. But May Donoghue’s 30-minute tram ride over the cobblestones of Strathclyde was to prove the start of a much longer, and truly momentous, journey — a journey that would take her to the House of Lords in London, there to unlock forever those vaulted chambers of the legal mind where lay, in timeless slumber, all the undiscovered categories of negligence. For us, her triumph was to be the start of an even longer journey through Lord Tennyson’s mist-shrouded “wilderness of single instances” in search of new standards of acceptable conduct between members of a civilized society. The end of our journey is not yet in sight.

When May Donoghue left her tenement home at 49 Kent Street, in the heart of Glasgow, she probably headed across London Road, down Greendyke Street, past the justiciary courts, over the Clyde by the Albert Bridge to the Gorbals, and so, through the countryside which is now taken by the suburbs of Bellhouston and Cardonald, to the ancient burgh of Paisley.

The Wellmeadow Café in the late 1920s. This is probably the only picture of the café in May Donoghue’s time. It is in the lower building on the right. A “Francis Minchella, confectioner” is listed in directories of the time as the occupant of these premises. The photograph was taken some time between 1926 and 1930 (remember the critical date, August 28, 1928). See the figure on the right. Could this be May Donoghue, heading for her appointment with destiny?

(Photo courtesy of the Old Paisley Society)

No doubt she alighted in front of the Thomas Coats Memorial Church, a few paces from the small building at the corner of High Street, Lady Lane, and Wellmeadow Street that housed Mr Minchella’s café. When she took her seat there, May Donoghue is said to have been with a friend. Of the identity of this mysterious person we know only one thing. It has been pointed out — to the annoyance of more romantically-inclined legal historians — that Lord Macmillan refers in his speech to May Donoghue’s companion as “she,”2 echoing perhaps a reference that had been made during argument. As my colleague Mr Justice Hamish Gow says, “those were not permissive times”; while separated from her husband, May Donoghue remained, of course, a married woman.

It was her friend — that unknown soldier on our roll of honour — who is said to have then given the short order that would change the course of legal history.

There are those who maintain that May Donoghue’s whole story of misadventure in Wellmeadow Street was simply a hoax — that it belongs to the rich heritage of Scottish legal mythology. Others have said that it all happened, but on another occasion, to someone else in Inverness. Sir Winston Churchill was dismayed that there were those who sought to cast doubt on the existence of King Arthur and his wonderful feats of chivalry. Surely must we likewise protest at these attempts — in the face of all the evidence — to deny to our law its most beloved figure, its greatest moment.

Let us then, as part of our pilgrimage, find as a fact — a fact of faith — that the long and stately procession of legal history did indeed pass through Paisley that August evening in 1928, so that May Donoghue might take her rightful place, and become at last the most celebrated litigant of all time.

The drama that ensued that evening at the Wellmeadow Café, which rightfully belongs to the civil law of Scotland, is known around the world to everyone who studies, teaches, practices, or decides what we all call “the common law.”

The café twenty-five years before. This is the only full-frontal picture so far discovered. It shows the café soon after the turn of the century. It is said to be quite possible that the small figure in front is the young May McAllister — she would then have been three or four years old!

(Photo courtesy of the Paisley Museum)

It is a great pleasure to discover how widely May Donoghue’s story is known also among civilians in Canada. Is it possible that she may perhaps yet perform for our own two jurisprudential solitudes the same catalytic function she has served for Britain’s civil and common law systems? In Claudais c. La Ferme St. Laurent Ltée,3 a decision of the Cour Supérieure du Québec, involving a mouse in butter, Mr Justice Meyer said:

La Cour croit bon de mentionner la décision dans la fameuse cause anglaise de M’Allister (or Donoghue) v. Stevenson (1932), A.C. 562, où la Chambre des pairs a décidé que, selon le droit écossais ou anglais, dans le cas d’aliments vendus par le manufacturer à un distributeur dans des circonstances qui empêchent le distributeur, ou l’ultimate acheteur ou consommateur, de découvrir par l’inspection un vice ou une défectuosité, le manufacturier á un devoir légal vis-á-vis l’ultimate acheteur ou consommateur d’agir comme un bon pére de famille et de voir á ce que l’article soit libre de tout vice ou défectuosité pouvant nuire á la santé. Il s’agissait en l’occurrence de la consommation d’une bouteille de soda contenant un escargot.

Surely May Donoghue would be surprised to know that the story of her immortal case has not only been told in many other lands, but told in Paisley in the French language!

At approximately 8:50 p.m. that evening in August 1928, May Donoghue’s friend is said to have ordered for her ice cream and ginger beer — the Scotsman’s ice cream float. Mr Minchella is said to have brought the ice cream in a tumbler and to have poured on it some ginger beer from a brown opaque bottle bearing the name “D. Stevenson, Glen Lane, Paisley”. It is said that after May Donoghue had taken a drink, and while her friend was refilling her glass, she saw, floating out of the bottle, what she believed to be the partly decomposed remains of a snail. May Donoghue said she was made ill by what she thought she had seen. She said she had to have medical treatment three days later, on August 29, 1928, from her doctor, and three weeks later, on September 16, 1928, at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

Original David Stevenson Bottle4. As pleaded in May Donoghue’s condescendence, the bottle is brown and opaque, its content completely incapable of intermediate examination.

(Photo by Michael Taylor)

Had it been her anonymous friend, rather than May Donoghue, who was served with snail-tainted ginger beer, the world would probably have heard nothing of it. The friend could have sued Mr Minchella, and, because there was a contract of sale between them, Mr Minchella would probably have had no defence. But the friend, so the pleadings say, chose instead to order “a pear and ice,” and presumably escaped unscathed.

Since May Donoghue had no contract with anyone, she would have to prove negligence if she were to recover. The only person she could sue for negligence was David Stevenson.

May Donoghue learned all this from a remarkable Glasgow solicitor and city councillor, Mr. Walter Leechman. Walter Leechman issued May Donoghue’s writ against Mr. Stevenson. It described the Stevenson plant as a place where “snails and the slimy trails of snails were frequently found,” and claimed £500 damages and costs. In due course Stevenson’s counsel moved the Court of Session to dismiss the claim, on the ground that it disclosed no cause of action. The motion failed at first before the Lord Ordinary, Lord Moncrieff,5 but succeeded 3-1 in the Second Division.6 The majority of the Scottish appeal judges followed a recent decision of their own in two cases brought by plaintiffs who claimed to have found a mouse in a bottle of ginger beer: Mullen v. A.G. Barr & Co.; McGowan v. A.G. Barr & Co.7 The majority declared that the only difference between those cases and May Donoghue’s was the difference between a rodent and a gastropod, and that this, according to the law of Scotland, amounted to no difference at all. The manufacturer of such products, they held, owed no duty of care to an ultimate consumer unless the consumer had a contract with the manufacturer requiring such care — a most unlikely situation.

It was against this decision that Mrs. May M’Alister, or Donoghue, sought her relief before “His Majesty the King in his Court of Parliament.”

A perusal of the Scottish Session Cases discloses the first reason why it must be said that fate had ordained for May Donoghue a place of honour in the cavalcade of legal history.

The reports show not only that Walter Leechman’s firm had acted for the unsuccessful pursuers in the mouse cases, but also that he caused May Donoghue’s writ to be issued less than three weeks after the appeal decision in the mouse cases was handed down. No doubt there was a reason — several come to mind — why the mouse cases could not themselves have gone to the House of Lords. If Mr. Leechman had not had May Donoghue’s case on the back burner, so to speak, who knows for how long the law might have remained as the Court of Session had declared it. How lucky for May Donoghue — how lucky for us — that she consulted perhaps the only lawyer in the world who would not only have taken her case, but have taken it to the highest court in the land.

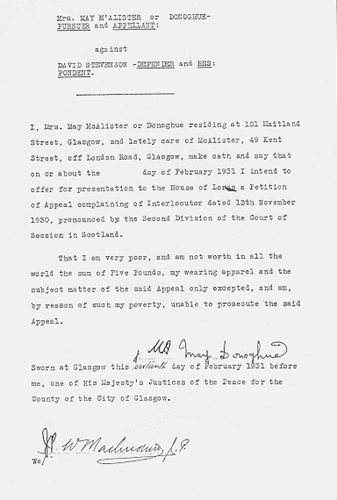

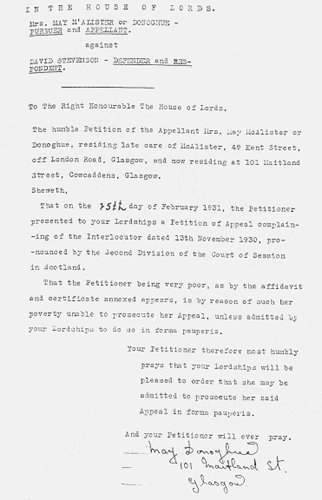

May Donoghue’s journey to that last tribunal cannot have been an easy one. Not only did she have to retain counsel who were willing to act without reward, but she had also to gain for herself the status of pauper, for there was no way she could have put up security for costs. The progress of May Donoghue’s petition to be allowed to appear in forma pauperis is recorded in the Lords’ Journal.8 It was supported by an affidavit in which she swore, “I am very poor. I am not worth five pounds in all the world.” Attached was a certificate of poverty signed by the minister and two elders of her church. On March 17, 1931, her petition came from committee to the assembled House, consisting of the Lord Chancellor, Lord Sankey, the Duke of Wellington, two bishops, two marquesses, twenty-four earls, sixteen viscounts, and eighty-eight barons, among them Lord Atkin of Aberdovey. In such distinguished company, including many of the greatest names of British history, was May Donoghue declared to be a pauper, with all the privileges attaching to that status before their Lordships’ House.

May Donoghue’s Petition. This is the petition signed by May Donoghue by which she sought leave to bring her appeal before the House of Lords in forma pauperis. In this way she avoided the need to post security for the costs which would have been payable to David Stevenson had her appeal been dismissed.

(From the original in the Records of the House of Lords)

May Donoghue’s Affidavit. “I am very poor,” she swears, “and am not worth in all the world the sum of Five Pounds”. Attached to her affidavit was a certificate attesting that May Donoghue is a “very poor person,” signed by the minister and elders of her church in Glasgow.

(From the original in the Records of the House of Lords)

And so it came to pass, nine months later, on December 10, 1931, in a committee room of the House of Lords overlooking the gardens beside the Thames where tea is served, that five Law Lords, dressed as is their custom in ordinary suits, sat before a fireplace to hear argument in May Donoghue’s case.9

Surrounded by tapestries in this English country-house setting, Lords Buckmaster, Atkin, Tomlin, Thankerton, and Macmillan heard submissions based mainly on the law of England, laid down almost forty years earlier by the Master of the Rolls, Lord Esher, in Le Lievre v. Gould10 and Heaven v. Pender.11 Counsel for May Donoghue were George Morton, K.C., and W. R. Milligan, of the Scottish Bar. David Stevenson was represented by W.G. Normand, K.C., Solicitor General for Scotland, J.L. Clyde, a veteran of the “mouse” cases, and T. Elder Jones, of the English Bar. Time does not permit me to say more of these counsel than that Mr. Normand was to become a Law Lord — and later to describe May Donoghue’s case to British Columbia’s David Roberts, Q.C., as “a hoax” — and that Mr. Milligan raced Lord Birkenhead around the Cambridge quadrangle immortalized in “Chariots of Fire,” and went on to become Lord Advocate at the same time that Mr. Clyde was appointed Lord President of the Court of Session.

May Donoghue’s counsel wisely rested her case on very narrow ground. A manufacturer who puts on the market an article intended for human consumption in a form that precludes the possibility of examination, they contended, must be liable to the consumer for any damage caused by want of reasonable care to ensure its fitness for consumption. Mr. Normand, for David Stevenson, laid emphasis on the wisdom of the Scottish appeal judges. The judge of first instance, Lord Moncrieff, had delivered “an elaborate opinion,” said Mr. Normand, “which seems to show — if this may be said without disrespect — a disinclination on his Lordship’s part to acquiesce in the law as it had been declared [i.e., in the “mouse” cases] rather than any real misapprehension regarding it.”12 Mr. Normand went on to make an always-potent point: the duty contended for, if it were to be affirmed, he said, “would be affirmed now for the first time” (emphasis added).

After two days of argument, counsel withdrew and the House took time for consideration.

While Walter Leechman and the counsel he retained had been contemplating the lamentable state of consumer protection law in Scotland, Lord Atkin’s mind had been engaged, at Westminster and at his Welsh seaside home, upon a larger but closely-related theme — and here is further evidence that May Donoghue’s journey was directed by the hand of fate.

On October 28, 1931, six weeks before argument was heard in May Donoghue’s case, Lord Atkin had given a lecture at King’s College, London, which foretold the future of our law of negligence.13 In his remarks, that evening, on the subject of “Law As An Educational Subject,” Lord Atkin declared:14

It is quite true that law and morality do not cover identical fields. No doubt morality extends beyond the more limited range in which you can lay down the definite prohibitions of law; but, apart from that, the British law has always necessarily ingrained in it moral teaching in this sense: that it lays down standards of honesty and plain dealing between man and man … He is not to injure his neighbour by acts of negligence; and that certainly covers a very large field of the law. I doubt whether the whole of the law of tort could not be comprised in the golden maim to do unto your neighbour as you would that he should do unto you.

And so it was that the great paragon of our law of negligence — our Good Neighbour — born unheralded in Wellmeadow Street on an August evening in 1928, came to be baptised quietly three years afterwards in the Strand.

Four months later, Lord Atkin was to issue his first formal announcement of the arrival of this newcomer among the personnae dramatis of our law. In Fardon v. Harcourt-Rivington,15 a decidedly unusual dog case, Lord Atkin spoke of what he called “the ordinary duty of a person to take care either that his animal or his chattel is not put to such a use as is likely to injure his neighbour,” an obligation he referred to as “the ordinary duty to take care in the cases put upon negligence.”

Another three months were to pass before Lord Atkin would lay before the legal world, as its example, the true character of this always-cautious and contemplative, but often unpredictable and potentially troublesome, person.

On May 26, 1932, Lord Atkin rose at last, amid the splendour of the great chamber of the House of Lords, to deliver his immortal speech in Donoghue v. Stevenson.16

Lord Atkin reminded the House of the words of Lord Esher in Le Lievre v. Gould:17 “If one man is near to another, or near to the property of another, a duty lies on him not to do that which may cause a personal injury to that other, or may injure his property.” Using the thoughts he had expressed the previous autumn at King’s College, Lord Atkin then melded Lord Esher’s dictum with the parable of the good Samaritan. Neighbourhood was a mental rather than a physical state. It would be enough to impose on David Stevenson a duty of care such that those in the position of May Donoghue ought to have been in his mind when he was bottling the ginger beer. She was his neighbour in spirit.

Lord Atkin made four statements, all of equal importance to any real understanding of his speech. He started with this fundamental caution:18

The liability for negligence, whether you style it such or treat it as in other systems as a species of “culpa”, is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. But acts or omissions which any moral code would censure cannot in a practical world be treated so as to give a right to every person injured by them to demand relief.

(In this statement Lord Atkin faithfully echoed his previous words at King’s College: “Law and morality do not cover identical fields”; “Morality extends beyond the more limited range in which you can lay down the definite prohibitions of law.”19)

Lord Atkin then stated his “neighbour principle”:20

You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be — persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.

(Here, again, was “the golden maxim” previously mentioned at King’s College, within which “the whole law of torts could be comprised,” and which Lord Atkin later applied in Fardon.21)

Three pages on, we find his second caution:22

I venture to say that in the branch of the law which deals with civil wrongs, dependent in England at any rate entirely upon the application by judges of general principles also formulated by judges, it is of particular importance to guard against the danger of stating propositions of law in wider terms than is necessary, lest essential factors be omitted in the wider survey and the inherent adaptability of English law be unduly restricted.

And sixteen pages further on, Lord Atkin stated the principle on which his judgement rested — the ratio decidendi of May Donoghue’s case:23

[A] manufacturer of products, which he sells in such a form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care.

It is for this simple statement of the law, the “products liability principle” let us call it — and for that alone, as its author was at pains to emphasize — that Lord Atkin’s decision in Donoghue v. Stevenson actually stands.

The principles laid down by Lord Atkin, himself an Australian, Welshman, or Irishman, were supported by two Scots, Lord Macmillan and Lord Thankerton, but vigorously opposed, of course, by Lord Buckmaster, who saw in them an invitation to chaos, a reversion to the laws of Babylon, and by Lord Tomlin, who referred to a recent railway disaster at Versailles to illustrate their dangerously broad and unprecedented scope.

The products liability principle in Donoghue v. Stevenson has proved capable of adaptation to the widest variety of situations in which damage of any sort is caused — personal injury, physical property damage, and pure economic loss.

If by his or her conduct any sort of producer induces reliance on the part of a consumer, the law may hold the producer liable — though there be no contract between them — should the consumer suffer foreseeable loss as a result of the producer’s failure to exercise reasonable care. The duty is one the producer must be taken to accept when seeking the trust of others, regardless of whether the product concerned be ginger beer, credit reports, legal or accounting advice, engineering services, or floor coverings. Professor Joe Smith has described the duty as being similar to the one enforced in the old action of assumpsit.24

What, then, of Lord Atkin’s great “neighbour principle,” the idea that for over sixty years has so gripped the imagination and perplexed the minds of lawyers the world over?

The neighbour principle considered in isolation — without regard for the large caveats that Lord Atkin so carefully placed on it — has, of course, been represented as a basis for imposing a duty of care in almost any case in which any sort of foreseeable loss is suffered by one person as a result of the action or inaction of another. It has been said by some to apply not only to cases of personal injury or physical damage to property, but also to cases in which there is no risk of either — that is, cases involving loss only to pocket or estate. It has been said to apply to nonfeasance and misfeasance alike. It has been thought by some that, directly or through his or her taxes, the ordinary citizen may be obliged in some circumstances to protect those fortunate enough to own property or investments against erosion of their economic position. Others ask, What of free enterprise? What of automation, price competition, security realization, the allocation of capital and resources, corporate takeovers, the vanishing corner store, the everlasting struggle for promotion, property, and profit? How, they ask, can there be a duty of care gratuitously for the economic interests of others, in the absence of an inducement to reliance, under such an economic system as ours?

One distinguished member of the House of Lords — not a Law Lord — is reputed to have observed, “The only way to make money is by taking it from other people.”

Surely Lord Atkin would be surprised, to say the least, at the confusion that has arisen between two of the principles he laid down in Donoghue v. Stevenson — his broad neighbour principle, on the one hand, which seems applicable only to cases of personal injury and physical damage to property, and his products liability principle, on the other hand, based on deliberately-induced reliance, which can be applied also in cases such as Hedley Byrne & Co. Ltd v. Heller & Partners Ltd.,25 where the only damage is to pocket or estate.

Perhaps it is this confusion between two essentially different principles that has served to keep May Donoghue’s case at the epicentre of seismic activity in the law of negligence.

The facts of Donoghue v. Stevenson are almost as controversial as its principles. Within the first quarter century after the decision, two English judges proclaimed that there never was a snail in May Donoghue’s ginger beer. In a speech in 1942, Lord Justice MacKinnon said, “When the law had been settled by the House of Lords, the case went back to Edinburgh to be tried on the facts. At that trial it was found that there never was a snail in the bottle at all. That intruding gastropod was as much a legal fiction as the Casual Ejector.”26 Lord Atkin’s biographer, Geoffrey Lewis, records that this story was traced by Lord Atkin through Lord Macmillan to a misstatement of something said to Lord Justice MacKinnon by none other than David Stevenson’s counsel, then Lord Normand.27 Twelve years later, in Adler v. Dickson, Lord Justice Jenkins said, “The House of Lords heard the preliminary issue in Donoghue v. Stevenson and when the trial was finally held there was no snail in the bottle at all.”28

It is no doubt as a consequence of these high judicial pronouncements that people have come to question whether there was a Wellmeadow Café, a May Donoghue, or a Mr. Stevenson — that there have, indeed, been misgivings about the bona fides of the Great Paisley Snail Case.

Our good friend, John Leechman, son of Walter Leechman and at the time principal of W.G. Leechman & Company of Glasgow, May Donoghue’s solicitors, provided us with much valuable material for our Festival in 1982. He also came to Vancouver to be our guest in September 1983, and at a dinner in his honour Mr Leechman asserted before us all that no such finding as the Lord Justices described was ever made. The trial they reported never took place. Professor Heuston29 and Vice-Chancellor Megarry30 confirm this. The reason there was no trial, as Mr. Leechman told us, is that David Stevenson’s executors paid £200 (not £100 as elsewhere stated) to end the matter. So the English judges of appeal had been guilty of what is called in the business “palpable and over-riding error”!

Why then, does May Donoghue’s case continue to hold such an enduring fascination for lawyers the world over?

The magnificent language of Lord Atkin, the profound mysteries of the neighbour principle, the clash between the Law Lords, as told in Professor Heuston’s splendid article31 on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the decision — this is the stuff of legal history. The meeting of the common and civil law worlds. The collision between principles of contract and tort law that started fifty years of jurisprudential upheaval. The contrast of sacred and mundane, splendour and poverty, the sublime and — at least in the manner of its pleading — the slightly ridiculous.

Surely there will never be such a case again!

How could there ever be such a litigant again as that determined lady — of whose difficult life something has at least been written by Alan Rodger32 — who was not worth five pounds in all the world, yet whose name has since become, in all the world, the cause of how many thousands and thousands of millions of pounds and dollars changing hands?

Is it because of the importance of the principles involved, then, or in spite of them, that the people of May Donoghue’s case also have their special place in our hall of fame? Lord Atkin and Lord Moncrieff, May Donoghue and her unidentified companion, David Stevenson and Francis Minchella, Walter Leechman, George Morton, W.F. Milligan, W.G. Normand, J.L. Clyde, and all the rest — what a wonderful company they make! If we smile when we speak of them now it is because we believe they would smile, too — whatever their former tribulations, surely they would smile with us now. We remember them when so many of their contemporaries — leaders of the Bar, ornaments of the Bench — are long forgotten, and it is they who have become the true immortals of our law.

Lord Atkin’s biographer Mr. Geoffrey Lewis has described some of the unassuming qualities of Lord Atkin, this great master of our law and language.33 Lord Atkin always rode the buses. Indeed he injured himself getting on a moving bus while a member of the Court of Appeal — not one bound for Clapham, but a Number 11 for Liverpool Street. Lord Atkin enjoyed detective stories, fast bicycle riding, and popular comedians. His daughter says he expected to be “treated with great disrespect at home,” which makes us all feel better. Lord Atkin loved the music halls, and to sing the songs that were sung there.

In paying our tribute to the people who gave to our law its greatest moment — who set it on a journey in search of new standards of acceptable behaviour in the modern world — let us imagine them all, in this magnificent hall sixty years ago, joining with Sir Harry Lauder in his favourite song — surely a worthy theme for May Donoghue’s journey, and for our own.

Though the way be long, let your heart be strong;

Keep right on to the end.

1 Originally published in Donoghue v Stevenson and the Modern Law of Negligence, Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia, 1991

2 Donoghue v. Stevenson, 1932 S.C. (H.L.) 31 at 61

3 C.S.M. 500-05-005996-72, October 17, 1975, Meyer J. (unreported).

4 The “genuine Stevenson bottle” is at present in the possession of the author

5 [1930] S.N. 117.

6 [1930] S.N. 138.

7 1929 S.C. 461

8 (1930-31), 163 Journal of the House of Lords 128, 152-3, 251

9 Supra, note 2.

10 [1893] 1 Q.B. 491 (C.A.).

11 (1883), 11 Q.B.D. 503 (C.A.).

12 Donoghue v. Stevenson, supra, note 2.

13 See (1932), J. of Society of Pub. Teachers of the Law 27.

14 As quoted in (1932) J. of Soc. of Pub. Teachers of Law 27 at 30 (also in G. Lewis, Lord Atkin (London: Butterworths, 1983) at 57-58) (emphasis added).

15 (1932), 48 T.L.R. 215 at 217 (H.L.) (emphasis added)

16 Supra, note 2.

17 Lord Atkin, ibid. at 581, quoting Lord Esher, supra, note 8 at 497 (emphasis added).

18 Ibid. at 580 (emphasis added).

19 Supra, note 13.

20 Supra, note 1 at 580 (emphasis added).

21 Supra, note 13.

22 Supra, note 2

23 Ibid.

24 J.C. Smith, Liability in Negligence (Toronto: Carswell, 1984) at 89.

25 [1964] A.C. 465, [1963] 2 All E.R. 575 (H.L.).

26 Presidential address of MacKinnon L.J., Univ. of Birmingham, Holdsworth Club, 1942.

27 G. Lewis, Lord Atkin, supra, note 14 at 52.

28 [1954] 1 W.L.R. 1482 at 1483 (Practice Note).

29 R.F.V. Heuston, “Donoghue v. Stevenson in Retrospect” (1957), 20 M.L.R. 1 at 2.

30 R.E. Megarry, Miscellany-at-Law (London: Stevens & Sons, 1955) at 81.

31 Supra, note 29.

32 Alan Rodger, “Mrs. Donoghue and Alfenus Varus” (1988), 41 Currently Legal Problems 1 at 3-9.

33 Supra, note 14 at 50.